Researchers at Manomet’s banding lab wonder how recent weather events will affect migratory birds this fall.

By Emily Renaud

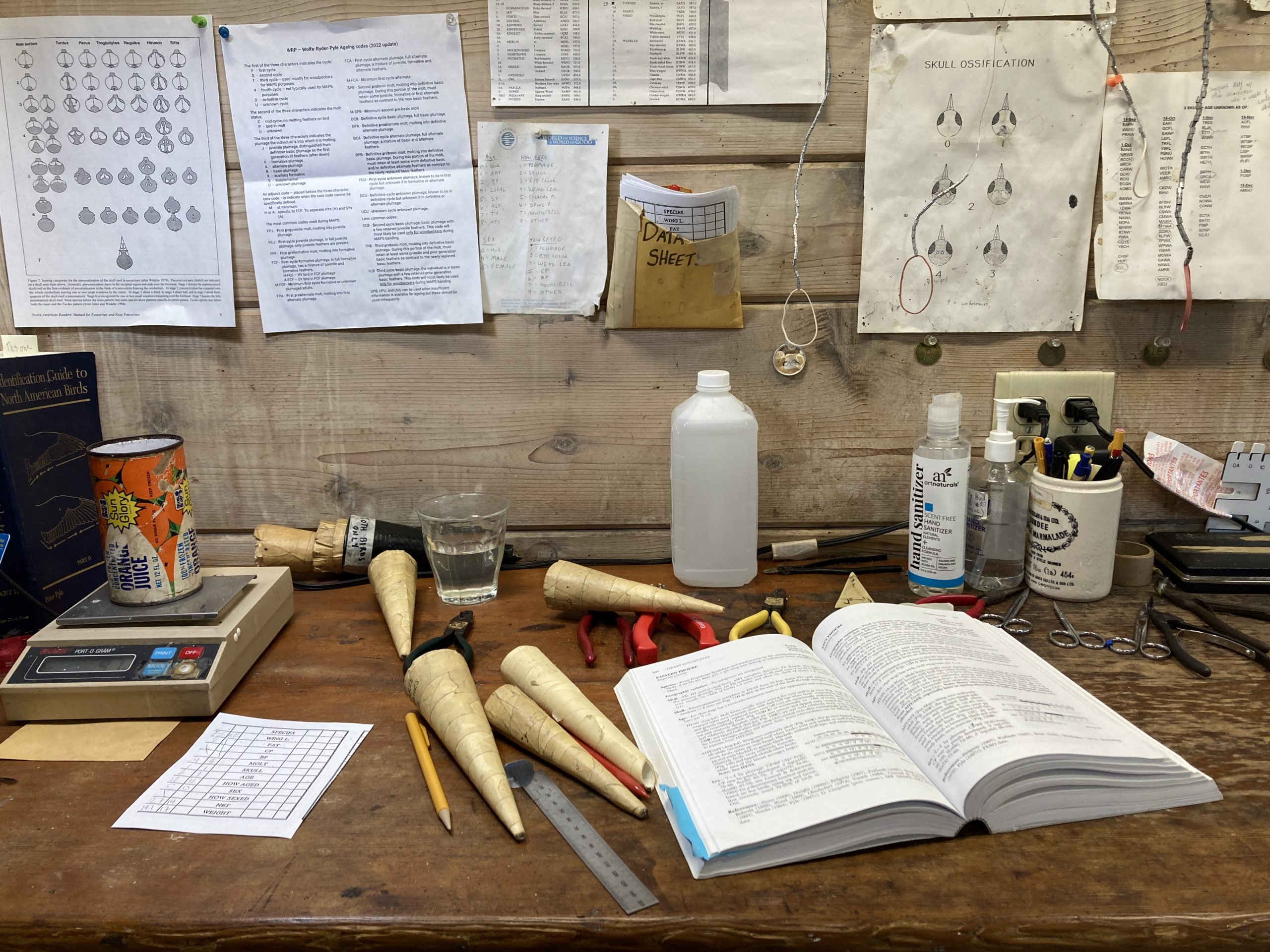

On August 15, for the 57th year, a team of seasonal biologists moved into the Widewater dorm at Manomet’s Plymouth headquarters. The crew of four — Amy Hogan, Emilia Skogen, Josephine Tagestad, and Sarah Duff — will live on-site through November 15, banding landbirds as they migrate through Massachusetts to their wintering grounds in the southeast U.S. and Central and South America. The data the banders collect will add to the nearly 60 years of consistent migratory bird research done at Manomet’s banding lab — one of the oldest banding labs in North America.

“60-year-old datasets don’t grow on trees. They’re the result of a lot of hard work and dedication,” says Evan Dalton, Director of the Manomet Observatory, which houses the banding lab and many of the education programs based at Manomet’s headquarters. “I think many [researchers] wish they had long-term datasets when they need to answer questions about things like population trends or seasonal changes, but they don’t often have access to them. We’re keeping that torch lit and using it to illuminate the questions of the present.”

Long-term datasets like that of Manomet’s banding lab have proven very useful when it comes to measuring environmental changes over several decades. Manomet’s data have contributed to studies analyzing changes in bird numbers and distribution in North America, like the “three billion birds” report published in 2019 revealing that over a quarter of birds found in the U.S. and Canada have vanished in the last 50 years.

“We [started banding] before any knowledge of climate change back in the 1960s,” says Dalton. “One of the starkest changes we’ve seen in our data over the years is how few of certain species we catch now compared to back then. Most of those are neotropical migratory birds or those we’ve lost a staggering amount of since the 1970s.”

Climate-driven impacts, including earlier springs and a higher frequency of extreme weather events, play a significant role in the type and number of birds found in Massachusetts today compared with 50 years ago. As the banding crew kicks off the fall season, Dalton wonders how this year’s weather patterns will affect migratory birds moving through the area in the coming months.

“We experienced one of the driest summers on record in Massachusetts this year. As droughts become more common during the summer, I’m curious how that will impact birds that rely heavily on fruiting trees and shrubs around Manomet’s headquarters,” he says. “Plant species like black cherry, for instance, started out well earlier this year. But as temperatures soared and weeks passed without hardly any rainfall, the trees eventually dropped all their berries.”

If this effect on food availability is only regional, it may not have much impact if birds need to go just 10 to 15 miles away to find berries. But if the drought affects a plant species’ entire range, some birds may be forced to find food elsewhere or settle for sub-optimal fuel sources.

“If we put a band on a bird and recapture it several more times that same day or week, we can assume it’s staying around here because there’s enough food for it to survive off of,” Dalton says. “Banding birds is one way we can monitor potential changes in food availability, but not the only way.”

This season’s crew has more than just banding on their to-do list. The team will also conduct various monitoring efforts across Manomet’s headquarters, including a weekly property census that ends with a sea watch of Cape Cod Bay to assess the number and diversity of birds using Manomet’s coastline. At the end of the season, the banders will have recorded valuable information on how birds and other wildlife use the property. The next seasonal team picks up these monitoring duties the following year, further adding to Manomet’s legacy of long-term data collection.

Now, two weeks into the banding season, all 50 of the lab’s mist nets are up and intercepting birds as they move through the area. Dalton and his team are eager to see what species this fall will bring, and he has his eye out for a few personal favorites.

“I’m excited for a new season and to work with this talented group of returning banders,” says Dalton. “We got a Yellow-breasted Chat the other day in the lab, so we’re off to a great start in my book.”

Follow Manomet on social media to meet this season’s banding crew!

Back to all

Back to all