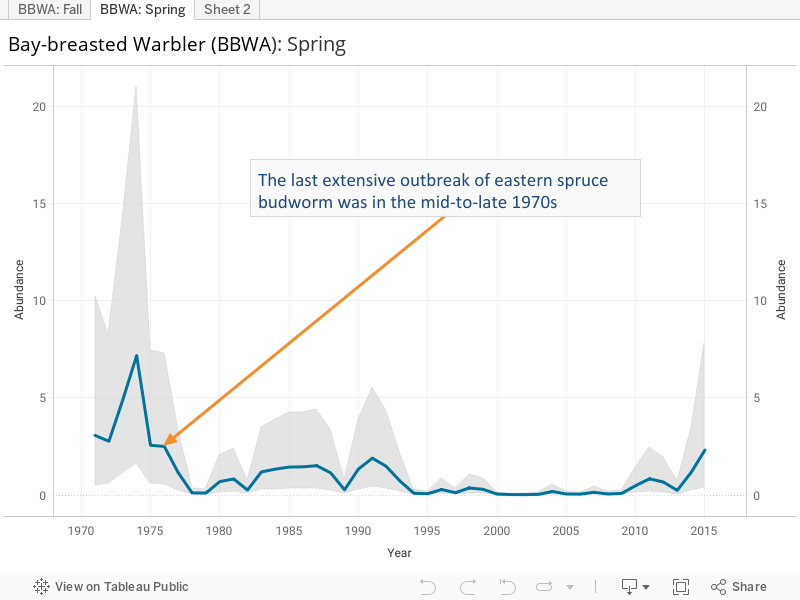

Nowadays, Bay-breasted Warblers are a rare treat in the Manomet banding lab. But in the mid-to-late 1970s, Manomet mist-nets were catching 50-100 Bay-breasted Warblers every fall. What caused their boom then, and why are they so sparse now?

Male Bay-breasted Warblers are unmistakable – they have a black face, a dark chestnut crown, and rust-colored throat, breast, and sides. Their high, weak song is a challenge to the hearing of ageing birders. Females are frequently flanked with a pale wash of this same rusty color, but their yellow-olive back and unmarked breast make them much harder to distinguish. In duller fall plumage, both are prime members of the myriad confusing fall warblers.

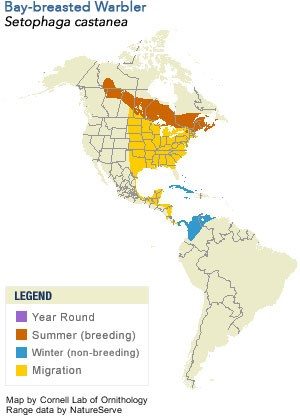

Bay-breasted Warblers breed in the boreal forest, mostly in Canada. They nest in mature stands of spruce and fir, often near water. They spend their winters among roaming multi-species flocks in lowland primary and secondary forests from Costa Rica and Panama to the northern corners of Colombia and Venezuela. During these winter months, they often feed on nectar, helping to pollinate plants in the tropical forest. But when they are back on their boreal breeding grounds, they fatten up on insects, and are especially fond of one particular caterpillar.

Spruce budworm is a native moth in spruce-fir forests, usually in numbers so low they are difficult to detect. But as these forest stands mature, the spruce budworm population can periodically explode, unleashing an abundance of larvae that feast on fir and spruce needles.

Today, targeted pesticides are often used to control these outbreaks as early as possible, but Bay-breasted Warblers and other boreal-breeding species can help naturally curb the damage caused by spruce budworm. Limited by the brief boreal breeding season, Bay-breasted Warblers only lay one brood per year, but they are known to take advantage of bursts in food availability to successfully raise more young. The last extensive outbreak of eastern spruce budworm was in the mid-to-late 1970s, and lasted until the mid-1980s. Does the graph below reveal an inextricable link? The last time the Manomet banding lab saw a boom of Bay-breasted Warblers was the last time the boreal forest was teeming with voracious (and nutritious) spruce budworm larvae. Do you also see a subtle long-term decline in their population trends? Why?

Back to all

Back to all