Manomet scientists and collaborators are pressing through rough camp conditions to complete key research objectives.

There is a famous saying based on the Thomas Wolfe novel of the same title: “you can’t go home again.” And if you do try, things will be very different than when you were there before. This year, we went back to the arctic, which feels like “home” to many of Manomet’s field biologists, and true to form things were very different!

The arctic is immense, so studying anything at the landscape scale is a huge undertaking. In 2000, we helped develop the Program for Regional and International Shorebird Monitoring (PRISM). In 2002, we launched our first team expedition with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Our first project? Surveying the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which had never been done.

We completed that survey, which took two years, in 2002 and 2004. It takes two seasons of fieldwork because the breeding season is short, and the landscape is large, so you can only get so many places while the birds are singing. The PRISM plan calls for repeating surveys of the entire Arctic every 15 to 20 years, and comparing population changes over the intervening years.

In 2019, we began the first season of repeating PRISM surveys in the Arctic Refuge, to monitor how shorebird populations since our first set of survey nearly two decades ago. There was an unusually early spring, so we rushed to finish the surveys while the birds were still displaying. After that, as was true with so many other things started that year, we put the second year of surveys (planned for spring 2020) on hold as the coronavirus pandemic spread rapidly.

By the time the virus was making every major headline in March 2020, we had already planned and organized the surveys and made all the arrangements. The unfolding pandemic stopped us in our tracks. We hoped by 2021 that COVID-19’s spread would have subsided enough to allow the project to resume. We once again made all the plans and arrangements, but the persistent pandemic thwarted us and we had to postpone again. Finally, this year things had improved enough that we could return to the arctic!

In addition to being huge, the arctic is also unforgiving. David Attenborough, the famous naturalist, describes the poles as “the coldest, windiest, most hostile to life” of any place on earth. We typically venture there in the relatively calm and warm spring, grateful that the harsh winter conditions have usually passed. But this year, we had the worst weather we have ever experienced in our 20 years of arctic work.

Experiencing winter in June

When I posted the previous blog entry from this year’s trip to the Arctic, I noted that while the crew left to set up camp on a sunny day, they then had to set up camp in the snow. Not terribly unusual. But when the wintery weather did not relent over the next day, it was unprecedented. We’ve had seemingly interminable three-day blows with sideways snow in many previous years. But this year we had highs of 27, accumulating snow, and winds blowing over 30 knots for almost two weeks.

This makes field camp cold and hostile, and wears down even the most hardy arctic biologists. What you can’t see in these photos is that the ceaseless wind made it nearly impossible to have a normal conversation as the wild flapping of the tents seemed to presage them flying off into the tundra at any moment. Luckily, our arctic gear served us well and all stayed put.

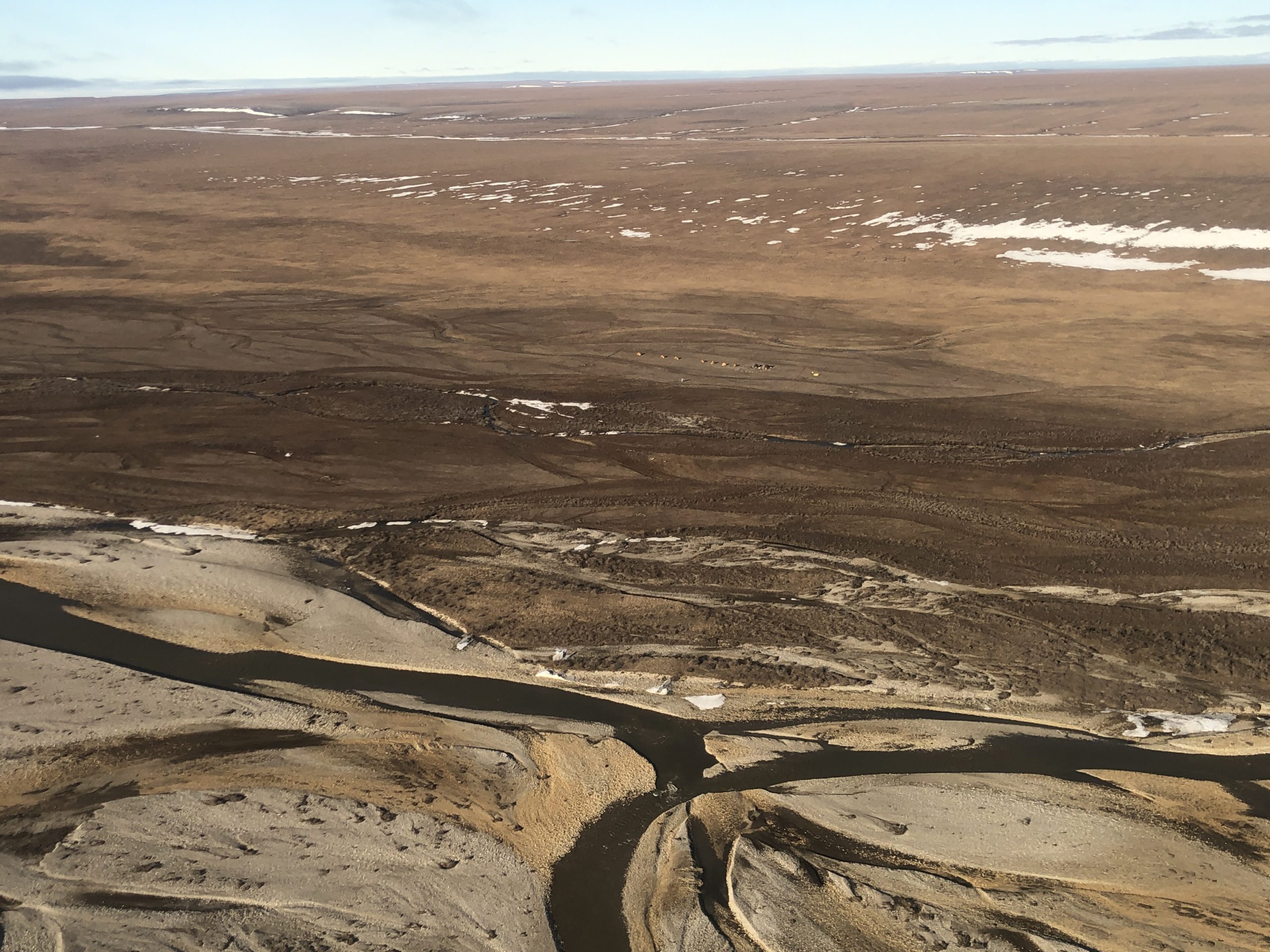

Much of our work in the arctic is supported by a small helicopter called a Robinson R-44. These relatively very small machines make it possible for us to access widely-dispersed research locations across the study area. They are capable of flying at cruising speeds of around 110 knots, or about 125 mph. On my flight in, I experienced something neither our pilot, Eryk, nor I had ever seen. The wind was directly against us, and as we attempted to fly up over a ridge of hills on the westernmost edge of the Arctic Refuge, our ground speed dropped to less than 10mph while our airspeed was unchanged. Eryk described this as resulting from laminar flow, where the wind, after cresting the ridge of hills by being forced up, then raced back down the other side, almost as fast as we were moving! We had to turn around, fly to a much higher altitude, and then slowly make our way forward.

When we finally arrived in camp, we redesigned most of our survey plans, since the weather had taken such a significant bite out of our field time. We have an excellent crew, and everyone worked together tirelessly to manage life in camp under the siege of the weather, do all the surveys we could, and rethink our plans daily as we worked to accomplish our tasks.

This got harder still when one of our crew, who had very briefly interacted with another crew at our staging site, came down with a very nasty bronchial infection (not COVID!) that then made its rounds among us. This is common in field camp, where everyone is close together. Despite his quarantining himself in his tent for days, and everyone masking…. as I write this, I am still getting over my turn with the camp illness. Several other camps in the region did get COVID infections, which dramatically altered their plans, but we managed to avoid that through careful preparations and a great deal of luck.

Pressing through all the challenges we faced, we did make it out onto the arctic landscape and conduct many of the surveys we had planned. One moment, while I was overlooking the Hulahula River, felt like a personal high point: as I watched, a rare opening of the clouds let some precious rays of sun shine down onto the landscape. To my south, I glimpsed an even rarer view of the Saddlerochit mountains, the northernmost outpost of Alaska’s Brooks Range.

I am relaying this account from the field, as I am now returning home. The crew is still working hard to wrap up the PRISM surveys, and is also working simultaneously on three other projects: researching the use of audio recordings of singing shorebirds to see if we can track population densities, satellite tracking of Whimbrels and American Golden-Plovers, and an assessment of shorebird nest success across the entire western end of the arctic coastal plain. We will post updates on all of these projects soon. I hope you will join me in sending the crew still on the ground warm thoughts, and wish them good weather and good luck as they work so hard to make contributions to shorebird conservation. Thank you again to all our supporters who made this work possible.

Back to all

Back to all