Mike Molnar

Director, Coastal Zone Initiative

With a changing climate and rising seas, our coastal salt marshes and intertidal ecosystems face three possible futures: they can grow fast enough to keep up, shift inland, or drown. When salt marsh accretion—the gradual buildup of sediment—can’t match the pace of sea-level rise, these ecosystems become increasingly inundated. Over time, flooding can convert a healthy salt marsh into a degraded habitat or even open water, leading to significant ecological loss. More than half the species of North American shorebirds experienced population losses greater than 50% over the last 30-years. The loss of additional coastal habitat that these birds rely upon is of great concern for all those working on shorebird recovery.

Salt marshes are far more than scenic landscapes. They provide critical habitat for species of conservation concern, support economically important fisheries, and act as natural buffers that protect coastal communities by absorbing storm impacts. A US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) study estimates that, from North Carolina through Georgia, sea-level rise and storm-surge flooding could result in an additional $2.2 billion in annualized economic losses over baseline conditions. Given this threat, it is paramount that we protect and restore our coastal and associated habitats for the benefit of current and future generations, wildlife and people alike.

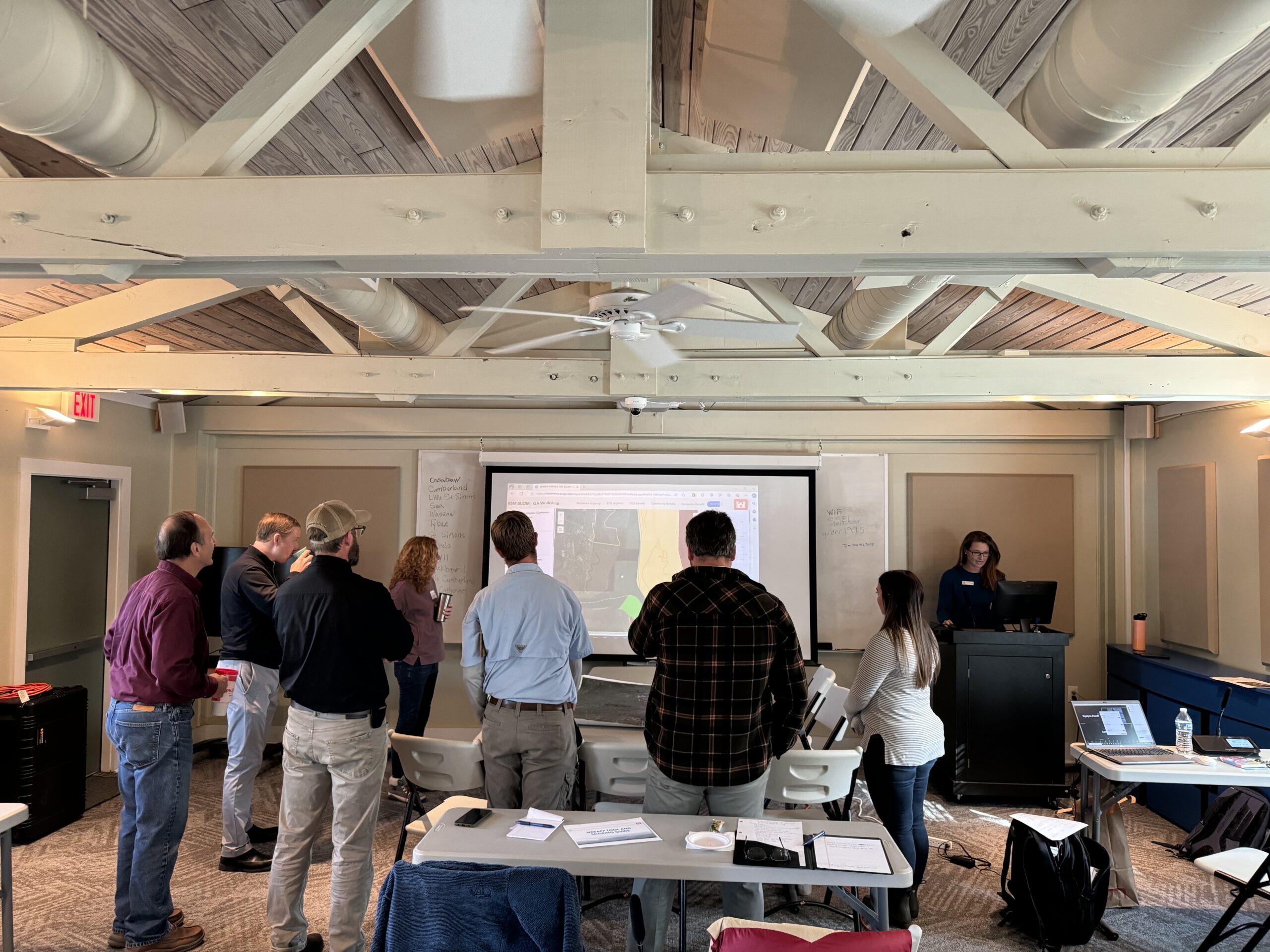

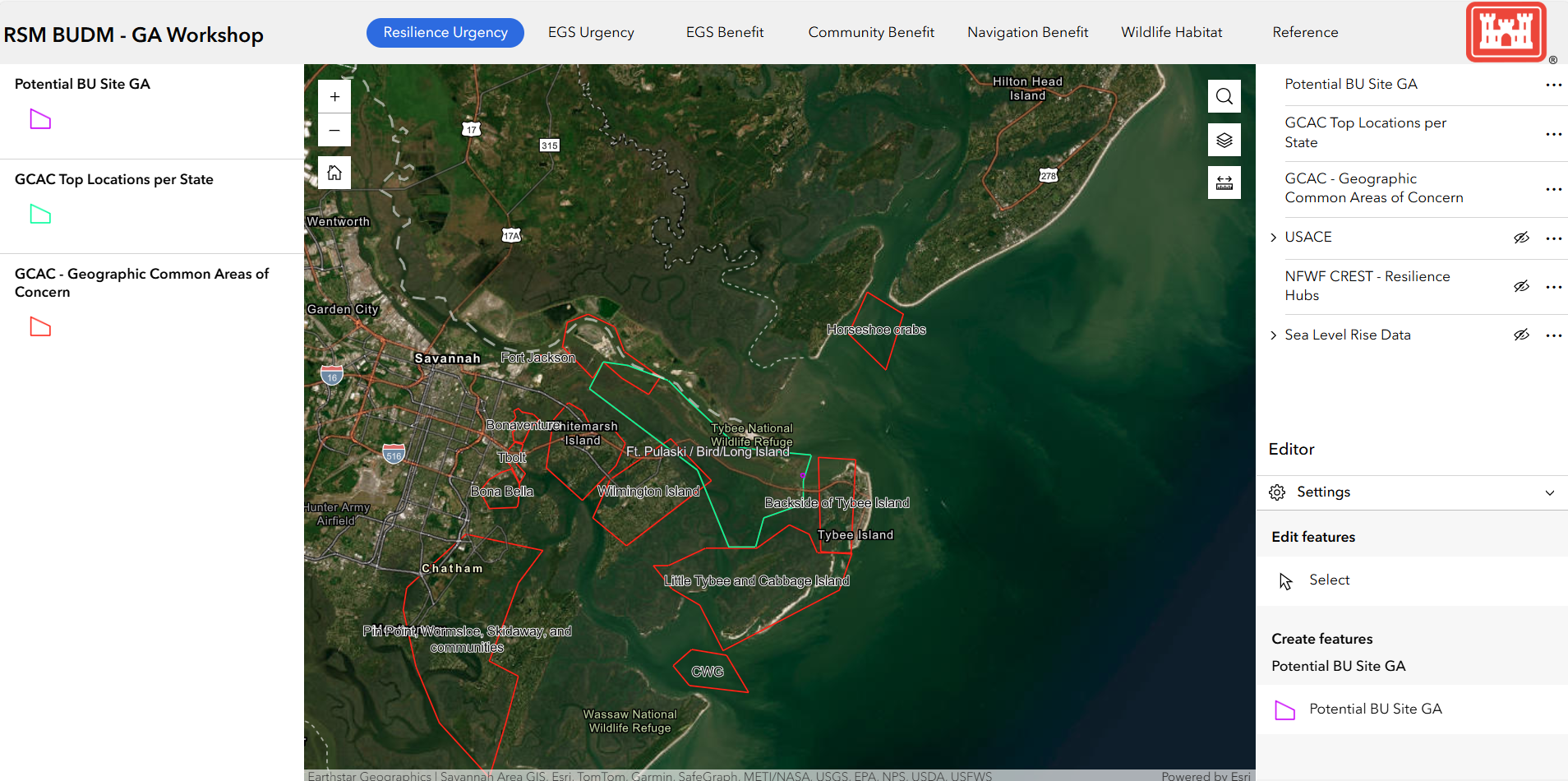

Manomet Conservation Sciences is working with a broad partnership to increase the resilience of our coastal ecosystems by beneficially using dredge materials (BUDM) in restoration actions to address the “grow” faster scenario. As part of this effort, staff from Manomet, Coastal States Organization, and US Army Corps of Engineers worked closely with other federal and state agencies, nonprofit organizations, and academic partners to identify coastal habitat restoration opportunity areas in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. Through our restoration prioritization workshops in these states, we identified 138 restoration opportunity areas and further refined the list to 12 priority restoration projects. These projects total approximately 4,500 acres of habitat restoration potential and tie in with future USACE dredging projects. Restoration of bird islands, coastal salt marsh, mudflats, and sand spits are a few of the options on the table. With the prioritization of these restoration projects, we set a roadmap to increase coastal habitat for shorebirds and improve the overall resiliency of these threatened coastal communities. (See our website for more information.)

Beyond identifying priority restoration areas, our collaborative next steps focus on getting projects into motion. That means moving from planning to action: designing restoration work, implementing it on the ground, monitoring its progress, and securing the funding needed to sustain every stage. We’re currently developing proposals in South Carolina and Georgia for restoration and working across state lines to create a shared monitoring framework that will help measure restoration success and guide adaptive management in the years ahead.

We’re optimistic that these efforts will bear fruit and are thankful to all the dedicated partners and funders involved. Stay tuned for future successes as we work together in support of this common cause.

Back to all

Back to all