In mid-July, amidst a sticky heat wave and with looming stacks of banding lab paperwork towering over our heads, Trevor Lloyd-Evans, Director of Landbird Conservation, agreed to sit with me in his office at Manomet’s headquarters and discuss some of the challenges he faces working in conservation biology today.

With Manomet’s annual Bird-a-Thon just around the corner (slotted for September 16 & 17), we chatted about some of the ways in which funds raised from this event help maintain our landbird programs’ extraordinarily long-term dataset and how they can propel its efforts further into the future.

Tell me about your role, and why you’ve found yourself doing what you’re doing.

I came here for a two-year stint in 1972, and I’m still here. If I ever have to go out and get a real job, I don’t know what I’ll do but the training here is certainly helping.

I have the traditional zoology degree, like everybody else, and I like birds and thought, “wouldn’t it be fun if I could do my zoology work in life, or at least start it off working with birds?” And so that’s what I did. There’s an organization in Britain called the British Trust for Ornithology which runs programs like censuses, bird ringing (banding), and all the esoteric parts of it—like recording nest contents and molt sequences. That’s where I started and got my basic training.

Why study birds?

(Laughing) Because they’re beautiful—and because we love to do it. This gets back to why we started the Landbird Conservation program at Manomet initially and why so many other people have started programs; birds are extremely sensitive environmental indicators. And that’s a tremendous benefit and has been true since peregrines and DDT, the canary in the coal mine, and since bird flu was spreading through the world; they are very sensitive and are a great organism to study, in general.

I think people have always regarded birds very positively. People just like birds and that’s an advantage if you’re trying to run a program and trying to get people interested in something slightly difficult to grasp, like climate change. You can show bird data and you’ve got their attention.

You’ve acquired decades’ worth of landbird data—one would imagine you want to keep collecting these data as long as possible.

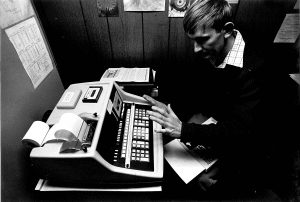

Manomet’s banding program was founded back in 1966 by our first director, Kathleen Anderson, and a group of bird-enthusiastic, adult volunteers (and students). That strong volunteer component is still very important today—and the word “volunteer” is a very good one in nonprofits; it’s very cost-effective! We have had students coming to Manomet from all over the United States, and also from the Netherlands, Germany, the U.K., Canada, Belize, Peru, and Columbia… I’ve probably forgotten a few, but we’ve managed to have people from all over, which is always a positive benefit.

We have our consistent mist nets locations—we run 50 nets—each of them is 40 feet long and seven feet high. Those require a lot of people (to maintain) and are expensive. We collect data on date, age, sex, measurements, fat, and weight and so on…and this allows for a much more precise conservation science approach to bird questions, even more than the very best of field observations.

The second aspect of Manomet’s work is data analysis; you can collect all the data in the world but if you don’t do anything with it, it’s just sitting there. So, we often work with other academics and organizations, which helps to address the important conservation questions that are illustrated so well by birds. These are questions regarding changes in population, or changes due to climate change, or questions that will affect people as well as birds—whatever happens to birds will happen to us soon after, so we’d better pay attention.

Another aspect is our program’s sheer longevity: we’re still going, we’re still collecting! The good news is that 50 years of data really helps you to detect the signal from the background noise; you can have “up” years and you can have “down” years, but over time you can really look at trends. And the education aspects that are associated with our research, which involves schools, colleges, adult groups, undergraduate training, and the climate lab that we’re running now from a National Science Foundation grant, are all great ways of passing the knowledge on.

How does funding help you maintain the work that your program does?

We want to maintain a continuation of long-term data that informs science-based conservation biology and policies. To do this, we need to fund at least two full-time staff and four seasonal staff positions just to keep our program going—that’s a challenge. We need equipment like the mist nets—we probably spend $4,000 a year just on mist nets alone, as well as all the other bits and pieces that go along with it. And then we need to offer free, or at least affordable, education programs.

So, this is where we ask our members and friends—and Bird-a-Thon is a great example, we’ve been doing this for a number of years—of where we need to fill in the gaps left behind by the economic retrenchment of much of our state and federal funding nowadays. As budgets get tight for everybody and research everywhere, we have to look ahead and say, “We need to keep these programs going.”

You’ll be participating in Bird-a-thon this year, seeing as you are the Director of Landbird Conservation. Have you got any spots where you’d like to participate this year?

Sure I’ll go birding; I’ll always go birding! You, and I, and many others in the past have been to Plum Island in the fall in the middle of migration. But we’re also relying on old banders and interns to put together a banding lab team to see if we can get some geographic coverage. I don’t know, we might see 400 species if we cover all of North America—maybe even Hawaii. It depends. But, we’ll get up early and be there by dawn, looking at birds—that’s the fun part of it. With support, we’ll raise important funds for the banding lab, which will be even better.”

Back to all

Back to all